|

Our Guide Published

Available from

Caliver Books

Buy it here

|

|

Note: In this part I have put some

information in square brackets and green italics that are not directly part of

the story but give an indication of how British fortunes were seen worldwide and

in Iraq.

Introduction

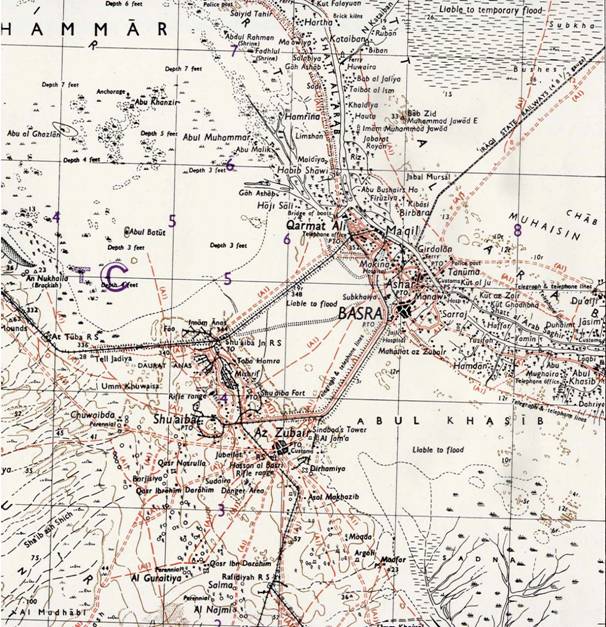

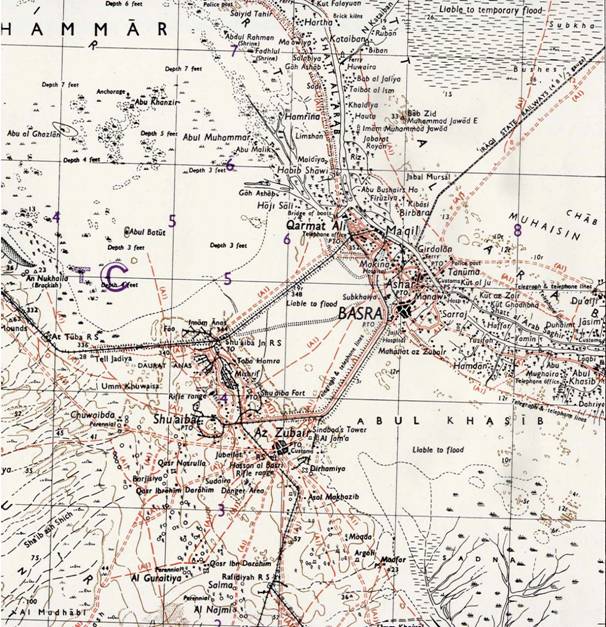

During the 1920s, Britain held a mandate that covered parts of the broken

Turkish Empire. The Kingdom of Iraq

was made up of the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates and the north western

fringe of the Great Arabian Desert.

The Hashemite, King Feisal, was pro-British and had been closely involved with

Lawrence in WW1.

In 1930 Iraq became a full member of the League of Nations and the Mandate

ended. A treaty was signed that

gave Britain the right to maintain two air bases, one at Shaibah, near Basra and

another at Habbaniya on the Euphrates sixty miles west of Baghdad.

These were maintained as way stations on the air route to India and the

Far East with the base at Habbaniya having access to a lake where the flying

boats of Imperial Airways could stage.

In addition, and very importantly, Britain retained the right to transit

troops through Iraq in both peace and war.

This treaty did not commit Iraq to become involved in any war on

Britain’s side but it did require Iraq to give “all possible facilities” for the

movement of the troops. Since there

were no British garrisons in Iraq the security of the air bases was entrusted to

the locally raised RAF Assyrian Levies, mainly members of the Christian

Nestorian community who were persecuted by the Muslim Iraqis although there

Kurdish and Arab companies as well.

The

Importance of Iraq in 1941

In 1941 it was American opinion that Britain would lose the war and this was

reflected in many of the other nations, particularly in the Middle East.

This was hardly surprising with Italy active in East Africa and Germany

in the Balkans following a string of victories across Europe.

The Axis seemed unstoppable.

Iraq, therefore, had a strategic importance to the British war effort.

It was, with Persia (Iran), the major source of oil for Britain outside

the USA. The oil pipelines ran from

Iraq to Tripoli in Vichy controlled Syria and to Haifa in Palestine.

The northern route was uncertain and had been closed.

The whole British war effort depended on the oil reaching Britain and

that depended upon there being no hostile action in Iraq.

Another factor made Iraq important in fighting the war; the treaty

allowed a short and direct route from India to the Middle East that was

relatively free from Axis interference (Italy was, for much of the early part of

the war, active in Somalia and Abyssinia).

This was, strategically, just as important in fighting Rommel as was the

oil the war effort in general.

Given the small number of troops available for operations in Palestine and

surrounding areas it was important that the Arab populations were not

antagonised to the extent that they took up arms.

The German Arabic propaganda broadcasts made capital out of the seemingly

unstoppable string of German victories to stir anti-British feelings.

The Japanese, though still nominally neutral, were also active in

undermining the British position.

Despite all this Iraq’s strategic importance seemed to escape both Britain and

Germany in the construction of their war plans.

The Anti-British Feeling and the “Golden Square” Coup

In 1933 King Feisal died and he was succeeded by his son Gazi.

Unlike his father he was not inclined to co-operate with Britain.

When he died in a road crash in 1939 he was succeeded by the 4-year-old

King Feisal II. However, the real

power was in the hands of the Regent Amir Abdul Illah.

Under his influence the Iraqi government, which was never very stable,

broke off diplomatic relations with Germany.

This was quite reluctantly done as anti-British feeling was running high

in several politicians. In 1940,

this feeling increased and Iraq maintained its relations with Italy despite its

entry into the war as part of the Axis and their Embassy constituted a major

communication route to the Axis.

The Italian Embassy was also the target of espionage activities by the British.

The achievements of German forces in Europe, North Africa and the Balkans

coupled with the propaganda broadcasts in Arabic gave support to the

anti-British campaign. The

anti-Semitism of the Nazis appealed those Arabs who resented British

interference in Arab affairs and British support for Jewish settlement in

Palestine. During December 1940 Rashid

Ali approached the Germans for aid against the British promising air bases and

cooperation with German forces in the region as well as access to Iraqi oil in

return for funding and equipment.

The equipment requested included 400 Light Machine Guns with ammunition, 50

light armoured cars, 100 batteries of Anti-Aircraft Artillery, individual

equipment, explosives, anti-armour missiles [sic] mines and 100,000 gas masks.

This was considered but not delivered.

When Greece fell to the Germans and the Afrika Korps advanced across North

Africa towards Egypt, the time seemed right for some pro-German Iraqi army

officers to stage a coup in and on 1 April they did so deposing the Prime

Minister, General Taha el-Hashimi. That night the Regent Emir Abdullah escaped

to the British Embassy and the next day he went to RAF Habbaniya in disguise and

later by air to Basra and out of the country on the British Gunboat HMS

Cockchafer.

[1 April, Rommel captures Mersa Brega.]

This new (illegal) Iraqi government did not

declare war on Britain but they did see an opportunity to advance their

republicanism through the Nazis who looked, just then, to be the winning side.

Yet another anti-British and anti-Jewish influence was the Mufti of

Jerusalem who had taken refuge in Baghdad.

He had written in his

memoirs:

Our fundamental condition for cooperating with Germany was a free hand to

eradicate every last Jew from Palestine and the Arab world. I asked Hitler for

an explicit undertaking to allow us to solve the Jewish problem in a manner

befitting our national and racial aspirations and according to the scientific

methods innovated by Germany in the handling of its Jews. The answer I got was:

'The Jews are yours.

Britain was in a difficult situation and emphasised that it intended to make

full use of the Treaty provisions to move troops through Iraq.

On the other hand Britain did not want to inflame the Middle

East by any action that might be seen as heavy handed.

Equally, another diversion of the scant military resources was

to be avoided. A

political solution was preferred and Sir Kinahan Cornwallis was appointed as

Ambassador but was not actually in post until 2 April too late to avert the

crisis by diplomatic means.

He arrived after the government in Iraq changed making Rashid Ali el

Gailani Prime Minister with the support of the Golden Square, four important

Army Colonels, Salah ed Din Sabbagh (Commander 3 Motorised Division), Kamil

Shabib (Commander 1 Division), Fahmi Said (commander Mechanised Force) and

Mahmud Salman (Air Force Chief).

His pro-German sympathies foreshadowed serious trouble.

He was believed, by British Intelligence, to be subsidised by,

if not actually in the pay of, the Germans.

Foreseeing potential problems ahead the War Office in London

asked Wavell, C-in-C Middle East, what forces he could deploy to Iraq in an

emergency. His

response that he had nothing available from his already stretched forces and

advocated a political solution did not go down well.

[3 April, Rommel captures Benghazi.]

Soon after his appointment Rashid Ali announced that his government would

re-establish diplomatic relations with Germany while fulfilling its

international agreements and specifically mentioning the Treaty with Britain.

The Regent was unable to prevent this movement towards the Axis and

German and Italian agents were active in drumming up support for Rashid Ali and

the Golden Square amongst the army, the police and the larger towns.

However, the desert tribes were more difficult to sway and mostly held

loyally to King Feisal II. With the

increasing support Rashid Ali set about arresting the Regent and gaining control

of the young King. Though as

already mentioned the Regent heard of the conspiracy on 31March and escaped to

the British Embassy and on to RAF Habbaniya hidden in a car.

The National Assembly, packed with Rashid Ali’s supporters, declared the Regent

deposed and Rashid Ali declared that that he was the leader of the “National

Defence Government”. Then on 6

April as the Germans invaded Greece and Yugoslavia, Air Vice-Marshall Smart, Air

Officer Commanding Iraq, asked for reinforcements from Egypt but his request was

denied. It would be going too far

to suggest that Baghdad and Berlin were cahoots at this time as the Germans must

have been concentrating their efforts on the plans for the invasion of the

Soviet Union. Indeed they had not

promised to lead a revolt but to aid one.

Nevertheless the new Iraqi government would have been encouraged by the

rapid and spectacular German successes and read into the German declaration more

than it actually contained. Coupled

to the mutual anti-Jewish policies of Arab and German it is not difficult to see

why the Iraqis ignored the German emphasis on the racial superiority of the

Arian concentrating mutual interests instead. The Germans, with no historical or

current colonial interest in the Middle East promised to support Arab

independence. These promises were,

as Hitler himself said, “a grandiose fraud”.

As a result of the Iraqi and Pan-Arab movement swallowing the promises

and propaganda line the Germans pursued this policy and it very nearly worked.

[6 April; German armies invade Greece and Yugoslavia.

7 April; Rommel captures Derna]

The deteriorating political situation led to some concentration of minds

and effort in London, Cairo and New Delhi.

There were no military forces in or near Iraq to support the meagre

forces in the two air bases. At

Shaibah, 16 miles from Basra was a single squadron of old bombers and at

Habbaniya was located No4 Service Flying Training School (SFTS).

RAF Habbaniya was an artificial oasis in the desert.

There were tree lined avenues, gardens, playing fields, and a golf

course. Riding stables housed the

polo ponies. Just over the

escarpment was the lake and yachting club.

The lake provided opportunities for open swimming while inside the fence

was the finest swimming pool in the RAF.

In addition there were 56 tennis courts and a superb gymnasium.

The emphasis was on leisure

rather than defence. The whole base

was surrounded by a high, 7 miles long, steel fence with two storey blockhouses

at intervals around it. The

main buildings, the six hangars, fuel and ammunition dumps, water supplies,

generators and the HQ were inside this fence but the runways were outside it.

The whole base was overlooked by a plateau just 1,000 yards away.

Defending the officers and men of the station, the civilian employees and

their wives and children was a battalion of levies who were mainly Assyrians but

alsoincluded Arabs and Kurds under Lt Col JA Brawn.

Supporting the defence was No1 Armoured Car Company RAF with 18 old Rolls

Royce armoured cars.

Throughout the diplomatic crisis the SFTS continued to send up training flights

while some junior officers with vision prepared the aircraft for action without

any official permission. These

preparations included fitting bomb racks onto the Audax, Oxford and some of the

Hart trainers to carry real bombs rather than practice ones and hand making

machine gun belts for the few antiquated Gloster Gladiator fighters used as

officers’ hacks there. These

preparations brought the target towing Gordon’s back into the bombing role with

a pair of 250lb bombs. The

Oxfords did have racks but only for eight 9lb smoke bombs and these were

replaced by racks for 20lb bombs, similarly for the Audax.

The few Hart bombers had their 250lb bomb racks reinstated but the Hart

trainers could not be armed at all.

All of this was done against resistance from the senior officers present and had

be accomplished at night and in secret.

It was fortunate for Habbaniya and British interests in the Middle East

that they ignored their commanders and proceeded.

Eventually AVM Smart agreed to put the base on a war footing and the

bulldozers levelled the golf course and polo pitch into an airstrip inside the

fence.

[15 April; British forces pushed back to Solum on the Egypt/Lybia border]

The

Crisis Deepens and 10 Indian Infantry Division Deploys to Iraq

On 16 April Cornwallis declared that Britain would be exercising its rights

under the Treaty. Immediately

following Cornwallis’ declaration of the intention to land forces the Iraqi

Government, on 17 April, requested military assistance from Germany if

hostilities with Britain ensued. On

the same day the first strategic deployment of British troops in war took place

when 364 Officers and Men of the under strength 1st Battalion the

King’s Own Royal Regiment (1/KORR) arrived at RAF Shaibah after flying in stages

from Karachi. The troops

brought only light equipment, small arms and 6 Vickers medium machine guns.

The only aircraft were old Valentias, half a dozen DC-2 civilian

airliners and 6 other aircraft variously reported as Atlanta or Hannibal

aircraft of Imperial Airways. These

troops were to ready to assist the disembarkation of 10 Indian Infantry Division

the next day.

Meanwhile, 10 Indian Infantry Division, commanded by Major General WAK Fraser,

from India been diverted before sailing its destination changed from Singapore

to Basra. The first brigade of the division, 20 Indian Infantry Brigade, had

sailed on 12 April in Convoy BP7 from Karachi and arrived in Basra on 18 April.

General Fraser’s instructions were:

1. To occupy the Basra – Shaibah

area in order to ensure the safe disembarkation of further reinforcements and to

enable a base to be established in that area.

2. In view of the uncertain

attitude of the Iraqi Army and local authorities, to face the possibility that

attempts might be made to oppose the disembarkation of this force, planning his

disembarkation in the closest concert with the Officer Commanding the Naval

Forces in the Persian Gulf.

3. Should the disembarkation be

opposed, to overcome the enemy by force and occupy suitable defensive positions

ashore as quickly as possible.

4. To take the greatest care not to

infringe the neutrality of Persia (Iran).

Major General GG Waterhouse, head of the British Military Mission to Iraq, with

a senior Iraqi Army officer, came on board and informed General Fraser that

there would be no opposition.

he

Iraqis were dug in all around the air base at Shaibah and Gen Fraser, of 10

Indian Infantry Division wanted to create an international incident while Gen

Waterhouse felt that it could be solved over a cup of coffee.

A compromise was reached and the CO went out in an armoured car to the

Iraqi trenches. There they found an

Iraqi sentry was seen walking on top of the trenches.

When he saw the armoured car he stooped, picked up his rifle and stood to

attention. He presumably thought

that someone very important was coming to inspect him.

20 Brigade took over the protection of the docks, the civil airport and the RAF

cantonment. This was fortunate as

the Brigade had not been loaded with an opposed disembarkation in mind but

rather logistically loaded to save on shipping space.

The Iraqis were not ready to put up a fight.

At Habbaniya Air Vice Marshal Smart got his first reinforcements in the

form of 6 Gladiators and 1 Blenheim from Egypt.

Things, for the moment appeared to be calm with both governments issuing

communiqués.

The British announced that “strong Imperial forces” had disembarked in

Basra to open the line of communications through Iraq in accordance with the

treaty. They went on stay that the

Iraqi Government was fulfilling its treaty obligations by giving full assistance

and facilities, that the local population had welcomed the troops and that they

hoped that the normal relations would soon be established.

The new Iraqi Government issued a similar communiqué which said that “the

comments made by certain foreign [i.e. Axis] broadcasting stations were

unfounded in fact”. At about same

time they again requested aid from the Germans.

This time they asked for 10 squadrons of aircraft, 50 light armoured cars

and captured British weapons because the Iraqi troops were familiar with them

including 400 Boys anti-tank rifles with 50,000 rounds of ammunition, 60

anti-tank guns with 60,000 rounds, 10,000 grenades, 600 Bren guns and 84 Vickers

guns.

Turkish diplomatic sources expressed their satisfaction at this

development as it marked a step in the direction of securing their routes to the

south.

Then on 27 April, the Rashid Ali and the Golden Square went back on what they

had said. They demanded that the

British land no more troops until the brigade already in Basra had departed from

Iraq and that the maximum force level on Iraqi soil was not to exceed brigade

strength. This was a direct

challenge and the British informed the Iraqis that they would ignore that

request. The British, therefore, took over the routes through Basra, thus

protecting their airbase at RAF Shaibah outside the city. With the rest of 20

Indian Infantry Brigade of 10 Indian Infantry Division due to arrive in Basra on

29 April the Ambassador chose not to inform the Iraqi government. As the

situation once again deteriorated Rashid Ali sent troops to occupy the oil

fields at Kirkuk and others to close the strategic pipeline to the British

Mandated port at Haifa while opening the northern pipeline to Vichy French

controlled Tripoli in Syria with the employees of the Anglo-Iraqi Petroleum

Company being badly treated in the process.

To rub salt in the wound he released long-term prisoners convicted of

attacking the British Consulate in Mosul in 1939.

When he heard the news of the imminent arrival of the second brigade he

refused permission for them to enter until the first brigade had “passed

through” despite his treaty obligations.

The British had no intention of passing through and no compromise was

possible.

It now seemed that Rashid Ali had decided upon a military confrontation.

In this he expected direct military support from the Axis Powers in time.

But he could not wait until it arrived because Britain had already stolen

a march by landing one brigade and with another about to land was likely to be

further ahead. He decided that the

appearance of the second brigade, which he could not oppose, would be the time

to move against RAF Habbaniya.

There is no doubt that he was counting upon the early arrival of German

aircraft, if not airborne troops, before the British took decisive action.

The German airborne troops, as we will see later, were earmarked for

another operation.

[22-29 April;

Germans and Italians force evacuation of Greece.

27 April; Germans enter Athens and Greece surrenders]

On 29 April, Rashid Ali allowed 240 British women and children to leave Baghdad

for Habbaniya. Another 350

sheltered in the British Embassy and a further 150 were offered hospitality in

the US Legation. Hundreds of others

who failed to reach sanctuary were interned by the Iraqis.

Reinforcements in the form of the 1/KORR, now 490 strong, were flown in to RAF

Habbaniya from RAF Shaibah in the same aircraft that had brought them from

Karachi. The Commanding Officer

went to Baghdad to meet the baggage party that arrived by rail.

There was quite a reception and as part of the deception plan he talked

about the “several Divisions” of British troops that were going to transit

through Iraq spending money and boosting the Iraqi economy.

Indeed three contracts were set for the construction of transit camps

with Iraqi contractors.

The King’s Own received three plane loads of equipment including Thompson SMGs.

These they had never seen before and the only way to unload them,

initially, was to fire off the magazine.

Air reinforcements arrived in Shaibah on 1 May in the form of 18 Wellington

bombers from Cairo. This was none

too soon as the next morning aerial reconnaissance showed thousands of Iraqi

troops supported by artillery and armoured cars on the plateau with more on the

way from Baghdad. Strange as it may

seem, the junior officers of this Iraqi force had been told that they were on a

training exercise. Though just how

many actually believed it is debateable since the troops were issued with live

ammunition but very little water and food.

In fact the stores held only 12 days of rations for the garrison and 4

days for the cantonment. Even at

this late stage Wavell, at Middle East Command in Cairo advocated a peaceful

solution. Had his argument held sway there is little doubt that the Golden

Square would have won a spectacular victory and Iraq could well have joined the

Axis camp.

The ground defence of Habbaniya was entrusted to Col Braund and his battalion of

Iraq Levies. Most of these troops

were Assyrian Christians. 1/KORR

was the mobile reserve and the RAF found some ancient transport for them and

this was supplemented by Iraqi trucks and 40 motorcycles bought in Baghdad.

The Battalion’s two Boys Anti Tank Rifles were mounted on armoured cars.

The King’s Own and others created temporary landing grounds within the

perimeter on the polo pitch and the playing fields because the main runways lay

outside the fence and was dominated by the plateau 1.000 yards away.

It

is interesting to know that the Iraqis had actually carried out a planning

exercise with the RAF to take Habbaniya should it ever be taken by a German coup

de main and so they had a plan.

However, and for unknown reasons, perhaps over confidence or that the

Golden Square were involved in more important political activity in Baghdad,

they did not attack. Instead the

Iraqis occupied the plateau, and dug in.

Iraqi troops began, in April, to piquet the bridge at Fallujah and also the

“iron bridge” over the Washash Canal leading to Baghdad.

As things deteriorated some RAF lorries with camouflaged loads took

sandbags, rifles, barbed wire and other items to the Embassy so that it could be

prepared for defence.

Rashid Ali gave permission, on 29 April, for all the British women and children

to leave Iraq. That afternoon 240

travelled to RAF Habbaniya. They

were the only ones to make the journey because of the movement of large Iraqi

forces from Baghdad on the Fallujah road.

Very early on 30 April the movement of the Iraqi columns was sent in a coded

radio message from the Embassy to RAF Habbaniya where training and

reconnaissance flights had been flown every day as had others to test the

improvised bomb racks on the Oxford and Audax trainers.

Yet more had been flown to “show the flag” over Baghdad.

That morning at 0600 two Iraqi officers delivered an

ultimatum to Air Vice Marshal Smart that he was to cease the flying operations

that had continued unabated throughout the crisis so far.

The ultimatum went on that they would open fire with artillery if any

British aircraft took off.

Since the plateau was only 1,000 yards from the air base the Iraqi positions

completely dominated it. In

addition, the runway now stood in no man’s land as it lay outside the fence.

Air reconnaissance confirmed that the

Iraqis had deployed some 50 pieces of artillery and 9,000 troops at Habbaniya,

as well as several times that number (no figures are available) of tribal

militiamen from the large towns. The tribal warriors were tough, undisciplined

and poorly led. On the ridge the

Iraqis were digging in, setting up anti-aircraft machine guns and light cannon,

and deploying artillery while armoured cars patrolled the flat ground between

the ridge and the air base. By 1

May the rebel forces covering the Cantonment at Habbaniya and the Baghdad to

Ramadi Road was estimated at one complete infantry brigade with most of the

Mechanised Brigade of two

mechanised battalions, one armoured car company, some tanks, a mechanised

Machine Gun Company, a Mechanised Signal Company, a combined AA and Anti-Tank

Company, a Mechanised artillery brigade (battalion) with additional forces north

of the river including howitzers and machine guns.

In Fallujah there was at least another infantry Company and a brigade at

Ramadi. On the way from Baghdad was

a horse drawn artillery brigade.

The ultimatum was refused and it was clear that the time had come for action.

So two pilots immediately volunteered and flew over the Iraqi positions.

They both returned safely.

Air Vice Marshal Smart, unwilling to start his own illegal little war,

temporised for the rest of 30 April and 1 May allowing preparations to be made.

He signalled the Embassy seeking permission to take such action as

necessary to protect his command. The

Iraqi artillery was of great concern and could easily wipe out the meagre air

force in RAF Habbaniya on the ground unless strong and immediate action was

taken. He was particularly

concerned that his ground forces had no artillery larger than a mortar and the

Iraq Levies were an unknown quantity.

The greatest threat came from a night attack since he would not be able

to mount air operations.

Fortunately, the local Iraqi commander was also hesitant to open hostilities.

Perhaps he lacked orders as the ultimatum had stated that they were there

to carry out a training exercise.

Many of the junior officers confirmed this and stated that they believed that

they were there to train not to attack.

Or perhaps Rashid Ali and the Golden Square had more pressing political

problems in Baghdad. Whatever the

case, the Iraqis also waited.

Air reconnaissance on 1 May drew no fire.

It did reveal that there were batteries on both sides of the river and

that the bund might be breached by shellfire thus flooding the base.

Later that day the Foreign Office gave Air Vice Marshal Smart authority to

launch air attacks at his discretion.

With this came a message from the Prime Minister couched in typical

language urging him to strike hard if he struck at all.

The

Opening Operations at RAF Habbaniya

And so, just before dawn on Friday 2 May the Iraq Levies and 1/KORR stood to and

heard the engines of the newly formed fighting strength of the RAF warm up and

then launch its pre-emptive strike that was relentlessly and ruthlessly pursued

attacking the Iraqi troops with their hastily converted training aircraft

piloted by instructors and students. They

were in four squadrons, three of “bombers” and one of fighters.

The Iraqis were taken by surprise as they prepared for morning prayers on

their holy day. Nevertheless they

soon responded to the attack with anti-aircraft fire and the immediate shelling

of the cantonment. The bombardment

could, on its own, have settled the issue if they had hit the power station and

the conspicuous water tower. During

later interrogation it was found that some of the Iraqi officers who had been

trained in Britain saw to it that the guns did little actual damage.

The aerial bombardment from Habbaniya and the Wellingtons from Shaibah

did little damage to the well dug in artillery pieces which were engaged when

their muzzle flashes revealed their positions.

The Iraqi infantry on the other hand were unwilling or unable to move and

stayed in their trenches and so took little part.

The infantry, therefore, suffered the morale sapping bombardment on

reduced food and water rations. The

Royal Iraqi Air Force intervened occasionally with fighter and bomber attacks

that hit several aircraft on the ground and inflicted casualties.

The Iraqi artillery fire was continuous but did not hit any of the

targets that would have ended the siege; the water tower or the generator.

That first day the RAF pressed home their attacks on the plateau.

AVM Smart was ordered to attack targets in Baghdad and wisely ignored

this selecting the more immediate targets on the plateau with his 63 aircraft.

They flew into intense the fire thrown up by Iraqi machine guns and light

anti-aircraft guns. These latter

guns were completely unexpected.

When 1/KORR cleared the plateau later they found that they were German in

origin. On that first day the RAF

lost 22 aircraft destroyed or badly damaged and ten of the pilots killed or

wounded. The Iraqi government

sequestered the oil assets and closed the Haifa pipeline while German and

Italian radio stations broadcast the Grand Mufti’s fatwa declaring Jihad against

the British.

Blood had now not only been shed at Habbaniya and also at Rutbah (1 May), a fort

in the Iraqi desert near the TransJordanian border, and near Basra (2 May).

On 1 May, at Rutbah, the garrison of Iraqi Desert Police opened fire on British

working parties on the Baghdad – Haifa road.

Lt Col Hammond, the chief engineer, managed to get most of his people

away to H4, a pumping station and airfield on the pipeline, in TransJordan about

130 miles from Rutbah. He and

eleven others were wounded.

Meanwhile, 21 Indian Infantry Brigade of the 10th Indian Infantry Division

landed at Basra on 29 April, secured the base there and at Shaibah.

On 2 May, the day of the start of the air attacks at Habbaniya, a mob of

dock workers refused to work on British vessels and approached the positions

held by 20 Indian Infantry Brigade.

They were dispersed when a couple of 25 pdr guns fired over their heads.

The Iraqi police were disarmed without a fight but the local authorities

were uncooperative. Some of the

local population took to looting shops and property.

Iraqi troops were known to be at Al Qrna, a village at the junction of

the Tigris, Euphrates and the Shatt al Arab and reputed site of the Garden of

Eden, and were attacked by the bombers of 244 Squadron from Shaibah.

It then set about clearing the area prior to moving north.

On 8 May they secured Ashar and thus the whole of the Basra – Shaibah

area.

The political situation was now tense with the likelihood of German

intervention through Vichy Syria or direct by air.

Rashid Ali’s government and the Golden Square, as usurpers, were not

popular with the other Arab countries and so it was not likely to be a rallying

point for them. The Embassy in

Baghdad lost it capability to use radio communications on 3 May but the

situation did not become a siege designed to starve them out.

It was possible to buy food at the gates and the siege was a great

inconvenience rather than a direct threat.

The main sign of the hostile action came from small boys who chalked rude

and offensive graffiti on the paving stones outside the Embassy walls.

Habforce Assembles in Palestine

AAt

the same time, General Wavell somewhat reluctantly, had been organising a mobile

force (Habforce) from Major General Clark’s 1st Cavalry Division.

He had lost all the equipment and nearly a quarter of the troops sent to

Greece and had ongoing operations north (Malta) and west (Libya) and south

(Abyssinia) as well as this new operation.

HABFORCE was based on Brigadier Kingstone’s 4th Cavalry Brigade with

the Household Cavalry Regiment (HCR), the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry and the

Warwickshire Yeomanry. The cavalry

regiments were in the process of converting from horses to trucks.

Thus they lacked trained drivers and mechanics.

In addition to the Brigade, Habforce was reinforced by the 1st

Battalion the Essex Regiment (1/Essex), a mechanised Regiment of the TJFF, The

Arab Legion, 60 Field Regiment Royal Artillery, an independent anti-tank troop,

a troop of 2nd Cheshire Field Squadron Royal Engineers and supporting

services. Its mission was to make

contact with the garrison at Habbaniya, secure H-4 and other points along the

route for future operations by the army and RAF and also to make contact with

the local tribes. This latter task

was to be ably performed by “Glubb’s Girls” as the Arab Legion became known from

their long hair and Arabic robes.

The force took some time to assemble in Palestine.

This brigade lacked training in its new role and was well short its full

complement of transport. Many of

its support vehicles were commandeered from civilian sources.

It also lacked tanks and armoured cars and had few aircraft.

Wavell regarded it as too weak to relieve RAF Habbaniya and left the

forces Palestine dangerously weak in the event that the Germans attacked through

pro-German Vichy Syria. This was

indisputable.

Major

General JGW Clark’s Habforce was “To

establish touch with the RAF Station at HABBANIYA and assist the garrison to

re-establish its defences, communications and supplies.

To assist in the evacuation of any personnel that may be necessary.

To keep open the L of C from TRANSJORDAN to HABBANIYA and to protect H4

and any operational landing grounds EAST of this station that may be required by

the RAF. To facilitate contact with

the tribes and counter revolutionary activities being organised by GHQ.

I divided HABFORCE into two portions and decided to send a Flying Column direct

across the desert to HABBANIYA and to retain the main body to guard the lines of

communication.

The composition of these two Columns was as follows:-

|

Main Body

HABFORCE

HQ 1 Cav Div &Sigs

Royal Wilts Yeo

Warwickshire Yeo

1 Essex less 2 Coys

166 Lt Fd Amb less Det

8 Lt Fd Hyg Sec

Cav Bde Gp Wkshop

Div Sec 1 Cav Div Ord Fd Pk

Det 1 Cav Div Postal Unit

1 Cav Div Pro Sqn less 2 Secs

Mech Regt TJFF

60 Fd Regt RA less 1 Bty and 1 Tp

1 Sub Sec Boring Sec RE

|

Flying Column

KINGCOL

Based on Brigadier Kingstone’s 4th Cavalry Brigade

HQ 4 Cav Bde & Sigs

HCR

One Bty 60 Fd Regt RA

1 Ind A/Tk Tp RA

Det 2 Fd Sqn RE

Two Coys 1 ESSEX with det carrier pl

Det 166 Lt Fd Amb

3 Res MT Coy RASC

552 Coy RASC

Desert Mech Regt Arab Legion less Det

8 Armd Cars RAF

|

On 2 May at 1030 Lt Col Nichols, Commanding Officer 1/Essex, was visiting the

staff college when he received a sudden order to report to Sub-Area HQ where “I

was ordered to assemble my battalion at H4 where I would form a firm base from

which I could operate against the Iraqi rebels, drive them from Rutbah and so

on. On arriving at H4 all troops

there, including RAF armoured cars (one section) would come under my command,

and that I would be directly under the GOC Palestine and Transjordan.

One company would move by train from Haifa at 1215.

All transport, including certain additional RASC vehicles, would move by

road at 1700 and the remainder of the battalion would entrain at 2000 to Lydda.

From Lydda the move to H4 would be by air”.

At 1615 that day he received his written confirmatory orders: “Your task is to

assemble your battalion at H4 with a view to occupying Rutbah and preventing

Iraquian [sic] troops from assisting a German landing should one take place

there. You should go from H4 to

Rutbah by air if possible, but your landing at Rutbah must be protected by our

troops, probably Arab Legion in MT.”

The battalion prepared as ordered but instead of the concentration taking place

he received orders to remain at short notice to move.

Only C Company (Capt JF Higson) actually moved up to Mafraq on 2 May, C

Company had actually moved out in about 1 hour from receipt of the orders and

was airborne a couple of hours later.

The order cancelling the move and ordering the return of the transport

arrived at 2000. Active assistance

from Germany was expected for the Iraqis and the battalion was to stand ready to

move forward at any time.

The first priority for this deployment was to secure the airfield at H4 and C

company of the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment was flown there and came

under the command of Air Vice Marshal d’Albiac.

H4 is about 10 acres of desert with a high perimeter wire fence.

Inside the compound are the large pumping units for the boosting the flow

through the oil pipeline. The

accommodation was good but had been looted by the Bedouin after the staff had

been evacuated when the Iraqi troubles began.

A squadron of the TransJordan Frontier Force (TJFF) and the Arab Legion

mechanised regiment, commanded by Major Glubb, followed them up soon afterwards.

The TJFF was an Imperial force with British Officers whereas the Arab

Legion was an allied force provided by Prince Abdullah of TransJordan. We shall

meet these legionnaires again later.

Operations around Habbaniya and the battle at Sinn el Dhibban

As these preparations gathered pace Air Vice Marshal Smart continued his

battle at Habbaniya. On 3 May and

on the following days his aircraft raided the military air base south of Baghdad

and the civil airport to the west

of the city. On 4 May aircraft from

Shaibah destroyed about 20 Iraqi aircraft on the ground.

The city and population of Baghdad was not attacked to reinforce that the

British had no wish to cause suffering to the

population with whom there was no quarrel.

Some of the aircraft dropped leaflets in Arabic assuring the

population that the British would defeat Rashid Ali and the Golden Square who

had betrayed them for German

gold. At this time the Regent

broadcast a message from Palestine appealing to the people not to be led astray

by “falsehood and lies which had brought the country from the blessings of peace

to the horrors of venomous war”.

Over the next five days, 4 SFTS launched 584 sorties, dropped 45 tons of bombs

and fired over 100,000 rounds of machine-gun ammunition.

Losses in aircraft and aircrew were high in the air and there were

casualties on the ground but the raids continued, on 5 may only 7 of the Oxfords

were serviceable. Air Vice Marshal

Smart widened his attacks to include Iraqi airfields and the Baghdad – Fallujah

road, a decision that might seem rash but was justified by events.

A welcome reinforcement of four Blenheim fighters arrived from Cairo on 4

May.

The initiative on the ground passed to the Assyrian Levies and 1/KORR and they

launched aggressive raids from the base while the Iraqi artillery and air force

did some minor damage. The main

targets of these raids were the guns on the north side of the Euphrates behind

the Burma Bund and the domination of the ground between the airfield and the

plateau. Both tasks were

successfully accomplished and the Iraqis thereafter withdrew their standing

patrols at night. An Iraqi attack

from the south by infantry supported by 3 light tanks and 8 armoured cars was

defeated by the infantry with Boys antitank rifles.

Machine gun fire from the blockhouses engaged any Iraqi movement and

positions observed. Later two

ancient 4.5” howitzers that had been guardians were brought back into service by

armourers and ammunition flown in.

The story was “revealed” to the Iraqis that the British had flown in heavy

Artillery and this had a devastating effect on morale far beyond their actual

effectiveness. At night the

British and Assyrian fighting patrols dominated no-man’s-land to the extent that

after a few nights the Iraqis withdrew their outposts and ceased patrolling.

However, the Iraqi artillery continued to shell during the night and air

patrols were sent out under extremely hazardous conditions.

The take-off was blind with the pilots relying of experience and

guesswork for take off and the landing scarcely better.

The landing lights on the runway could not be used and at least one

aircraft was lost. The intense air

operations terrified the Iraqi infantry and militiamen who began to flee on 6

May and by the next day the only Iraqi troops to be found were those running

from the British warplanes.

As all this was going on at Habbaniya the Royal Iraqi Air Force Rashid and

Ba’quba air bases around Baghdad came under attack from the Shaibah based

Wellingtons. They destroyed or

damaged about half the Iraqi air force’s offensive capability in two days.

The operations were having a devastating effect on the Iraqi air force as

an intercepted signals showed.

These declared that the Iraqis had almost exhausted their supply of bombs and

ammunition and requested immediate German aircraft support because their

aircraft were nearly all destroyed.

The army, likewise, was withdrawing short of artillery ammunition, rations and

water.

The garrison in Habbaniya, swollen by refugees and additional troops was

sustained by airborne “shopping trips” to Shaibah.

Although

the air raids on the artillery and infantry seemed to be causing little actual

damage the morale effect was building, particularly upon the infantry who had

little to do but endure the aerial bombardment.

The air attacks had a much greater effect on the roads.

Here supply and reinforcement convoys were attacked and destroyed.

The choke point at the Fallujah bridge was subjected to many destructive

raids. Then on the night of 5/6 May

1/KORR and the Assyrians raided Sinn el Dhibban (Arabic for “The Teeth of the

Wolf”) which lay between the river and the escarpment to the east of the air

base. Two companies from 1/KORR

were to assault the Iraqi positions.

The attack opened with the RAF armoured cars closing up to the village.

They were not fired upon.

Then as B Company of 1/KORR was near the village the Iraqis opened fire with

well sited and well concealed machine guns.

The attack stalled but the situation was restored by Armoured Cars from

No1 Armoured Car Company RAF, and a flank assault by D Company 1/KORR, the

levies , close support bombing and artillery fire from a couple of WW1 vintage

4.5” Howitzers. These had guarded

the gate until recently restored to fighting condition by the artificers of the

RA flown in with ammunition from Basra.

This was too much for the Iraqis and their fire slackened.

As the action closed the band arrived by air and went straight into

action because D Company had taken so many prisoners.

On the left 1/KORR swept through the village and stormed the high ground beyond.

On the right the Iraqis broke before the Assyrians reached them.

The Iraqis attempted to stem the retreat by bringing up motorised

infantry and artillery from Fallujah but these were destroyed by RAF aircraft.

First the rear of the column was destroyed then the head and the planes

flew 137 sorties up and down bombing the trapped column for 2 hours.

The ground flooded by the Iraqis effectively confining their own vehicles

to the road. The road was reported

as being a ribbon of fire when the raids ended with the loss of one Audax.

The Iraqis lost about 70 vehicles and 500 men during the day and by dawn

the whole force was in retreat eastwards.

Habbaniya had raised its own siege at comparatively little cost.

Then the troops took the plateau they found a large amount of equipment

abandoned there; six 3.7” Howitzers (some sources say these were Czech built),

three German light anti-aircraft guns, two anti-tank guns, one 18 pounder field

gun, thre Anti-tank rifles, 45 Bren guns, 11 Vickers machine guns, 2 Italian

machine guns, 10 modern armoured cars, one light tank, three dragons (gun

tractors), some carriers, 18 trucks, 6 motorcyles and 340 rifles and large

amounts of ammunition. From the

captured equipment, King’s Own was able to re-equip itself with modern small

arms and other weapons.

The battalion’s A Company manned the three captured AA guns in defence of

Habbaniya.

The aircraft from Shaibah had not been idle and had destroyed more Iraqi

aircraft of the ground at Baghdad and Ba’quba.

The barracks at Washash on the western side of Baghdad was also hit.

Later in the day a Gladiator dropped the news of the day’s successes to

Embassy in Baghdad. In these operations the RAF lost 13 aircrew killed, 21too

badly wounded to continue and 4 grounded with their nerve gone.

They recorded 647 sorties and, according to Dudgeon, many more

unrecorded, dropped 3,000 bombs and fired 116.000 rounds of ammunition.

By 9 May this motley collection of training aircraft largely crewed by

instructors and students had virtually destroyed the Royal Iraqi Air Force, and

with the ground forces, defeated and demoralised the besieging Iraqi army

inflicting heavy losses in men and equipment.

The effect of these joint operations was threefold.

The cantonment had held out and not been defeated thus depriving Rashid

Ali of the bargaining tool that he had intended to use to drag out negotiations

in a political crisis. He was

hoping that the Germans would arrive to support his army.

It appears that he did not expect the British to fight much less take the

offensive. Secondly, the failure to

capture the airfield deprived him of the the Germans of a safe route to fly in

airborne troops any further south than Mosul.

And thirdly the aerial bombardment had demoralised the Iraqi forces, and

not just those on the plateau, a blow from which they only recovered in part

later. Most importantly Rashid Ali

had lost face with the Iraqi people by not capturing RAF Habbaniya and by not

getting the German aid that he had promised over and over again.

Major General Clark stated, “Throughout

this very difficult period all ranks of the RAF conducted themselves in

accordance with the highest traditions of that service.

Every available aircraft was in constant action under the most difficult

conditions and the pilots of the training machines in particular did enormous

damage by persistently delivering low bombing and MG attacks in the face of

accurate and intense AA fire...

One

excellent example of this was provided by

a closely packed convoy of over 40 enemy vehicles which was completely

put out of action near Canal Turn whilst bringing reinforcements from FALLUJAH.

There, destroyed in its tracks, it remained for weeks afterwards, a grim

example of the necessity for dispersal against aerial attack.”

Operations

around Basra

As the Iraqis withdrew from Habbaniya on 6 May, the 21st Indian

Infantry Brigade arrived by convoy in Basra.

The brigade comprised 4/13th Frontier Force Rifles, 2/4th

and 2/10th Gurkha Rifles.

Also with this convoy were 2 troops of the 13th Lancers with

Chevrolet Crossley Armoured cars and a detachment of Indian Sappers.

More troops arrived the next day and Lieutenant General EP Quinan to

command what was later to become “Iraqforce”.

These reinforcements allowed further offensive operations in and around Basra.

The telegraph and wireless stations were taken and snipers caused a few

casualties amongst the Gurkhas. The

Iraqi civil administration stayed away from their offices and, for a time the

dockers and dredger crews refused to go to work.

The forces on Basra an Shaibah expanded their area of control and

established the lines of communication.

Iraqis

request German Assistance and Vichy Compliance

Eventually responding to Iraqi requests the Germans started to prepare a

shipment of arms in April but these were never sent.

The size of the shipment and its composition is worth noting as it could

have had a significant effect.

Earmarked for Iraq were 15,000 Dutch rifles with 5 million rounds, 600 Dutch

LMGs with 6 million rounds, 200 French 13.2mm Heavy Machine guns with 2 million

rounds, 50 French 8mm mortars with 25,000 bombs and 110 French 50mm mortars with

75,000 bombs. Why this was held

back is not clear but maybe it was because of the later requests for ex-British

equipment.

The Iraqis had since requested more German help and this arrived in the form of

weapons and ammunition from ex-British stocks captured at Dunkirk as well as

French equipment from Vichy Syria.

During May the French sent four loads of military supplies, two trainloads of

aviation fuel and a battery of artillery.

These arrived too late for use and depleted French stocks that they were

to need later in the year. The

equipment from Vichy Syria included; 15,500 Lebel rifles, 200 Hotchkiss 8 mm

machine guns with 5 million rounds of ammunition; 354 Sub Machine guns (probably

MAS) with 88,850 cartridges, four 75 mm guns with 10,000 shells, eight 155mm

guns with 6.000 shells and 30,000 hand grenades.

None of this material was used due, mainly to a lack of time and

instructors. The signs of German

assistance became real on 7 May when the first Luftwaffe transport aircraft

landed on Vichy airstrips in Syria where they were given every facility by the

French.

It had taken very little time for Berlin to acquire the Vichy government’s

permission to utilize Syria for the proposed plan. The Vichy French, who seemed

quite optimistic that the Germans would succeed in Iraq, on 8 May confirmed the

following concessions:

(a) The stocks of French arms under Italian control in Syria to be made

available for transportation to Iraq;

(b) Assistance in the forwarding of arms shipments of other origin that arrive

in Syria by land or by sea for Iraq;

(c) Permission for German planes, destined for Iraq, to make intermediate

landings and to take on fuel in Syria;

(d) Cession to Iraq of reconnaissance, fighter and bomber planes, as well as

bombs, from the air force permitted for Syria under the armistice treaty;

(e) An airfield in Syria to be made available especially for the intermediate

landing of German planes;

(f) Until such an airfield has been made available, an order to be issued to all

airfields in Syria to assist German planes making intermediate landings.

Vichy, in return for assisting Germany, were permitted to rearm six

French destroyers and seven torpedo boats, to relax the stringent travel and

traffic regulations between the zones of France, and to arrange for a

substantial reduction of the costs of occupation.

Rashid Ali received £10,000 in gold and the Grand Mufti $15,000 in banknotes on

9 May and on 21 May a further £10,000 in gold and $10,000 in banknotes arrived

for them respectively. A further

shipment of £80,000 in gold reached Athens but was not delivered as hostilities

had collapsed by then. The

first real signs of German aid came on 10 May with the arrival of the Reich’s

newly appointed representative to Iraq, Dr. Fritz Grobba. Accompanying the Nazi

official were two Heinkel He 111 bombers. Further additions to the Iraqi

arsenal, over the next few days, included a squadron each of He 111bombers and

Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters.

Meanwhile, a few days later, Rudolph Rahn, a special foreign ministry envoy,

arrived in Syria to organise the proposed flow of munitions to Iraq.

Rahn’s efforts produced the first

arrival of supplies into Mosul on 13 May.

This force included ground crews and a small anti-aircraft detachment.

Intelligence was now reporting that

Rashid Ali was losing the confidence of his supporters through hid repeated

failure to live up to his promises.

He had also become fearful for the future.

On the British side the command of operations had transferred to General

Auchinleck in India on 18 April had reverted to Wavell on 5 May.

Wavell had allocated all the forces that he could spare and feared any

further drain. He thought that the

retreat of the Iraqis from Habbaniya signalled an opportunity for a diplomatic

solution. Auchinleck, on the other hand,

advocated energetic military action against the Iraqi Army and to secure key

strategic sites like the oil fields and pipelines.

Lieutenant General Quinan had left India with orders to take direct action and

to expect a German invasion through Syria.

However, Wavell gave him orders to do no more than secure the Basra area.

Clark also received orders to advance on Baghdad and make contact with

the Ambassador. The relief was to

come from the west, not the south.

I any case, the forces at Basra still had 300 miles of flooded land to cover

against the 80 miles from Habbaniya.

Thus a force of a few hundred was sent to overawe, bluff and brush aside

several thousand opponents.

The British air attacks continued on Iraqi bases in Baghdad, Erbil, Mosul and Al

Musaiyib. The first Luftwaffe raid

on Habbaniya took place on 10 May, on 13 May the Axis force flew more bombing

missions but was hampered by a lack of fuel and on 15 May a He 111 attacked the

lead elements of Kingcol in the desert.

On 16 May three German fighters attacked Habbaniya and losses were

sustained on both sides. The Iraqis

compounded the effect of the British raids by shooting a German plane over

Baghdad killing Major Alex Blomberg who had arrived to lead the Luftwaffe

operations in Iraq, though Grobba says that he was killed by an RAF fighter when

he arrived in the midst of an air battle.

The Italians also sent support in the form of 11 Fiat CR-42 biplane

fighters from 155 Fighter Squadron commanded by Captain Sforza. The

British responded by flying in aircraft reinforcements from Palestine and the

Desert Air Force including Blenheims, Hurricanes and Tomahawks. The air route

from Syria was closed by RAF bombers from Palestine attacking the Vichy air

fields from the night of 14/15 May and the rest of the month, destroying

equipment and several Vichy and German aircraft on the ground.

Habforce and Kingcol

We will now return to Habforce. We

left them with their forward elements at H-4.

The Flying column assembled in various places and concentrated at H4 on

11 May with about 2,000 troops and 600 vehicles and crossed into Iraq on 13 May.

They drove on to H-3, the next pumping station, and there they met

Squadron Leader Casano with No2 Armoured Car Company RAF.

He reported that they had already been in action and with the Arab Legion

had taken Rutbah fort. This good

news came just after the TJFF had refused to cross the border into Iraq forcing

Brig Kingstone to use the Yeomanry to guard his line of communication.

Major

May’s detachment of A and D Companies of 1/Essex with two carriers from the

Carrier Platoon had left Haifa on 11 May to rendezvous with Kingcol in Mafraq

(Transjordan) that evening. They moved on to H4 on the 12 May.

4

is about 10 acres of desert with a high perimeter wire fence.

Inside the compound are the large pumping units for the boosting the flow

through the oil pipeline. The

accommodation was good but had been looted by the Bedouin after the staff had

been evacuated when the Iraqi troubles began.

The Battalion replenished at overnight halt with fuel and water and moved

on the next day with Kingcol to Rutbah.

Rutbah is a squalid collection of Arab hutments with the usual children

and dogs staring at the troops and trucks passing through.

The Rest House was fairly smart but had been ransacked by the Bedouins.

Nothing of value remained.

On 9 May RAF Blenheims had made an ineffective raid on the Iraqi Desert Police

in Rutbah in support of the Arab Legion.

The bombers were met by defensive rifle fire that shot down a Blenheim,

killing its crew. The Arab Legion,

lacking any weapons heavier than a machine gun, could not take the fort.

A old enemy, Fawzi al Qawukji (pictured left), had appeared with 40

truck-loads of well armed police and insurgents.

The attentions of the bombers, the armoured cars and the Arab Legion

persuaded the police to depart and the fort was found deserted on 11 May.

[11 May Rudolph Hess flies to Scotland.]

The

way was opened up for Habforce and it departed on 11 May, arriving at H3 on 12

May under orders to conduct a war of manoeuvre.

The fighting portion of the column, Kingcol, was now made up of the

Household Cavalry regiment, 2 companies and the 2 Bren carriers of 1/Essex, a

Field Regiment RA, an anti-tank troop, an AA troop and a troop of Royal

Engineers with 2 RASC transport companies carrying everything that the column

would need; combat supplies (fuel, ammunition, rations and so on) as well as

spare parts and other equipment.

Water, in particular would be a particular problem.

On 13 May the water ration was reduced to half a gallon a day as they

passed through H3. When the column

reached Rutbah, which was now held by the Arab Legion, Brig Kingstone was

informed that the Iraqis held Ramadi but this was nearly unapproachable because

of the flooding. The next Iraqi

forces appeared to those withdrawing from Habbaniya to Fallujah.

They now occupied positions overlooking the bridge over the Euphrates

west of the town. "Rutbah

is a squalid collection of Arab hutments with the usual children and dogs

staring at the troops and trucks passing through.

The Rest House was fairly smart but had been ransacked by the Bedouins.

Nothing of value remained."

[13 May; USSR recognises the Rashid Ali Regime.]

On 15 May the column set off for eastwards for Habbaniya at a steady

convoy speed of 17 miles in the hour.

This allowed for halts along the way every two hours.

They covered 160 miles over desert tracks reaching “Kilo 25” a marker on

the track showing that they were 15 miles from Ramadi.

As already noted that day saw raids on the column by a “Blenheim bomber

in Iraqi markings” though it was probably a He

111 bomber. This was followed by

another attack by Bf 110 fighters.

The column fought back with a few machine guns and saw some individual acts of

heroism from the Arab Legion in particular.

The column suffered some casualties.

A group of officers from Kingcol HQ searched for water for the vehicles

and found it at an area where natural asphalt was taken to be used on the

roadway. The water lay on top of

the asphalt. The officers,

including Somerset de Chair, took off their boots to paddle in the water only to

find they sank a little and the asphalt took a long time to clean off their

feet.

James Glass, an RASC

driver from Currie near Edinburgh, recalls the tactics.

“Our camping arrangements were

interesting. We went into "leagar - as the Roman Legions did - as North American

settlers did. We drove round into a huge square, two deep. In the centre we

settled the ambulances and Field Hospital, also the HQ and Signals. The Signals

busied themselves putting up the aerials and transmitters, and setting up the

connections. The Field Artillery on the perimeter turned their 25lb guns round

facing outwards at the ready. Then the little scout cars went out, about a mile

- we could see them with their flares at the ready in case of surprise attacks.

At this stage, no attack was expected, but practice was essential. During the

day, one "spotter" plane surveyed the area...

Every

pumping station on the line was a small fort...

they were every 100 miles or so. Inside the fort perimeter were the

water wells, pumps for the oil, civvi houses and a small landing strip. Only a

small plane could use the landing strip - mostly Lysanders.”

Before dawn the following day they set off again expecting to reach Habbaniya

that evening. The Arab Legion was

sent off to protect the flanks. At

first all went well then the 3 tonners of the RASC started to sink into the

sand. After continuous hard work in

the ferocious sun they made it back to Kilometre 25.

They had lost only a few of the supply trucks but the situation was now

close to desperate with a shortage of fuel and water.

Next morning the Arab Legion scouted ahead and led the column over the desert to

Habbaniya by way of Mujara, a group of buildings and engineering yards south of

the lake. The route was difficult

and would have been almost impossible without the Arab Legionnaires.

As Captain Greene of the Essex

says “the normal firm desert gave way to numerous small serrated wadis

which appeared to run across our main axis, and, except for their main course,

were of soft sand. Unless a vehicle

took them at high speed the wheels sank to the axles.

Most of that day was spent on this most uncomfortable ride.

By late afternoon the column reached the firmer ground of the plateau and

arrived in Habbaniya by the evening.”

The Habbaniya defenders had repaired the bridge here and guarded it.

In Habbaniya they found that the RAF clubs and bars were well stocked and

open though food was scarce. In the

early morning of 18 May a troop of the Household Cavalry on patrol near Ramadi

was fired on by the Iraqis. Later

that morning Kingcol set off once more and despite another air attack that

caused casualties it bivouacked at Mujara.

Its arrival almost coincided with the Habbaniya defenders setting off to

Fallujah.

On the same day as Kingcol reached Habbaniya, Major General Clark (GOC Habforce)

and Air Vice Marshal d’Albiac who was the new AOC Iraq, arrived by air, Air Vice

Marshal Smart having been injured in a car crash.

Kingcol captures

Fallujah Bridge

The defenders had received reinforcements by air in the form of the rest of

1/Essex from H-4 and elements of 2/4 Gurkhas from Basra.

And now that the first part of the operation had been successfully

concluded with the relief of RAF Habbaniya the second object, a salutary lesson

to the rebels, had still to be accomplished.

The capture of the bridge at Fallujah was one of the most brilliant operations

in the whole of the war. The plan

was made by Colonel Ouvry Roberts as commander of the “Habbaniya Brigade” and

was one of the very few occasions where land and air forces operated under a

single commander with a unified command.

The problem he faced seemed almost impossible without landing craft, specialised

equipment and considerable artillery support.

The approach to the bridge was restricted to a single causeway, Hammond’s

Bund, and that had been breached several miles from the bridge.

Colonel Roberts plan was to ferry 2/7 Gurkha Rifles over the Euphrates on

an improvised “flying bridge” (two steel hawser ferry) on the night of 17/18

May. By dawn they were to be in

positions along the northern edge of Fallujah.

The KORR (some sources say only C Company and others say 2 Companies) was

to be landed by air behind the town to cut it off from reserves from Baghdad.

The

Advance on Fallujah was to be made on both sides of the river.

Major General Clark’s report on the action is as follows:

The

Advance on Fallujah was to be made on both sides of the river.

Major General Clark’s report on the action is as follows:

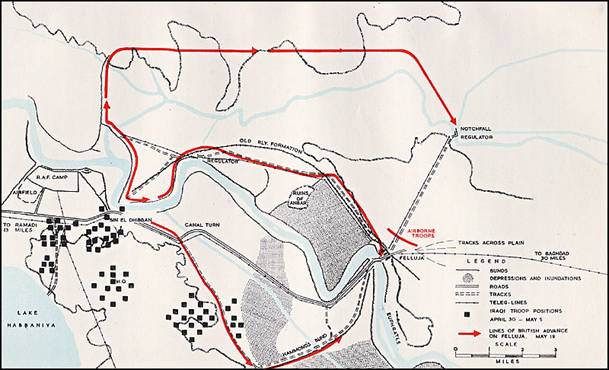

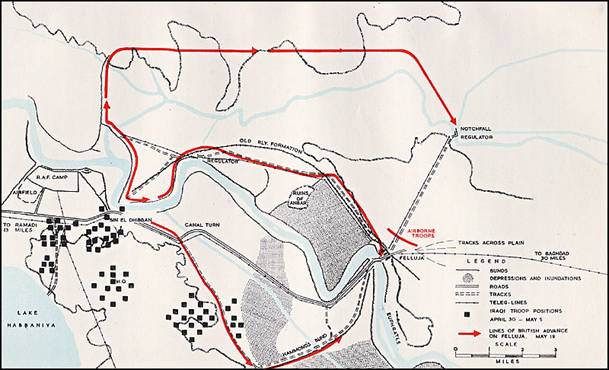

Col Roberts therefore called a conference of Commanding Officers on 15 May and

discussed plans for the capture of FALLUJAH with the bridge intact.

The Method decided upon was a combined air and ground attack preceded, the day

before, by a bombing attack on located targets at RAMADI in conjunction with a

feint attack by ground troops.

The capture of the town itself was to be carried out by the air striking force

in conjunction with the operations of columns called G, A, S, V & L Columns.

G Column was to prevent enemy interference with the FALLUJAH Bridge and to cover

the repairs to Hammond’s Bund.

A Column was to capture the Police Post

and Regulator Bridge 1 mile West of SAKHLAWIYA and the advance towards

FALLUJAH and take up a position on the high ground North of FALLUJAH covering

the exits from the outskirts of the town.

S Column was to cross the ferry immediately after A Column and support that

Column when it moved up to FALLUJAH.

It was to protect A Column from the direction of SAKHLAWIYA and form a

secure base to cover the withdrawal of A Column which it was to reinforce if

necessary.

V Column, airborne, was to take up position 2000 yards from the outskirts of

FALLUJAH, covering the road FALLUJAH – BAGHDAD, by fire, thus preventing the

exit of enemy troops from FALLUJAH.

L Column was to cross the Euphrates by ferry behind S Column and move up to

Burma Bund to establish a ferry across Notch Fall Regulator and provide a line

of withdrawal or a line of evacuation for prisoners, at the same time supporting

V Column.

Meanwhile a small detachment of RE and a troop of artillery from KINGCOL were to

assist the Sappers and Miners in maintaining the ferry North of SIN EL DHIBBAN,

reconstructing Hammond’s Bund and providing ferry facilities as SAKHLAWIYA

Regulator and Notch Fall Regulator.

The air striking force, in co-operation with the land forces were to bomb

located targets in FALLUJAH, drop pamphlets calling on the garrison to surrender

an then continue bombing in their own time until requested to stop by Brigade HQ

or a smoke signal from G Column.

Fighter patrols were to be maintained over the area, with instruction to report

by W/T if V Column was being attacked in strength.

A River Flotilla was to organized by moving boats from the Lake to keep

communications across the river at SIN EL DHIBBAN and the ferry was to be

protected by AALMG posts.

The original intention was to put this plan into operation on 19 May, the RAMADI

feint taking place on the day previously.

Upon this day also it was intended that KINGCOL should arrive in

HABBANIYA. This was not to be,

however, as the Column ran into a patch of bad going and became sand-bogged in

trying to find a way round the South of the Lake.

Whilst reconnoitring a new route, I flew from H4 to HABBANIYA to assume

command of the ground forces. At

this point I shall leave HABFORCE, in this account, until I have dealt with the

operations which were being carried out at FALLUJAH.

On my arrival at HABBANIYA I was greeted by an enemy air attack.

Three He.3’s (Sic) shot up the cantonment from an astonishingly low

altitude for half an hour. They

were eventually intercepted by our aircraft , however, and one enemy aircraft

was believed lost another being damaged.

Apart from this, two of our aircraft on reconnaissance over RASHID

attacked two Me 110’s during the morning and both enemy machines were shot down

in flames. In the evening the RAF

attached MOSUL twice, setting two aircraft on fire and damaging another and one

large monoplane was set on fire, several others being probably damaged.

Our aircraft also carried out extensive bombing and reconnaissance work

as well. It will be seen that this

was a day of considerable aerial activity.

At this time it was becoming increasingly evident that German aircraft were

likely to operate in considerable numbers from SYRIA.

Aircraft of the Palestine Command had attacked German aircraft at PALMYRA

twice on the 15th and done considerable damage as the enemy aircraft

were attacked at RAYAK and DAMASCUS.

As the result of this German activity, I postponed the attack on FALLUJAH until

I could get a clearer picture of the probability of German aircraft taking a

hand in the operations.

Meanwhile, on 17 May, as a result of information received, a Column under

command of Lt Col Brawn composed of One Company of Iraq Levies, commanded by

Capt Graham, a nephew of Brigadier Malise Graham, with four 3.7 How under Major

Couper, RA carried out a small but successful operation just EAST of SUTTAIH

BRIDGE and one sec MMG’s and a Mortar fired on a new MG post on the Bund whilst

two Pls Levies moved North and combed the big palm grove along the river bank

for about 3 miles. They returned in

the evening having taken 16 prisoners and discovered some hidden arms.

The evacuation of Iraq Levy families by air now commenced and 84 persons were

flown to PALESTINE during the next two days.

A portion of KINGCOL, after overcoming its obstacles, arrived in HABBANIYA on 17

May, having spent the night at MUJARA BRIDGE.

Further reinforcements also arrived in the form of 45 ranks of the Essex

Regiment including 3 officers by air from H4 and 100 Gurkhas airborne from

BASRA. These latter were quartered

in the Levy Lines.

The forces at HABBANIYA were increasing and the RAF had been successful in

destroying considerable enemy petrol supplies.

This, together with other important factors, indicated that the time was

opportune for the capture of ALLUJAH and 19 May was chosen at that date.

The plan finally adopted was identical with that described above, except that

the feint on RAMADI was not carried out lest it should attract the attention of

German aircraft. The various tasks

were allotted as follows:-

|

G Column

A Column

S Column

V Column

L Column

|

Commander:- Capt Graham

Troops:- One

Coy Iraq Levies

One Pl Iraq Levies

In Support One Tp 25pdr guns RA (6 guns from KINGCOL)

Detachment Sappers and Miners

Commander:- Capt Anderson

Troops:- One Coy Iraq

Levies

Detachment Sappers and Miners

Commander:- Major

Strickland, 2/4 GR

Troops:- Detachment

2/4 GR

Under command One Tp HABBANIYA Artillery (5 3.7How)

Commander:- Lieut DJ Rees,

King’s Own

Troops:- One Coy

King’s Own

One sec MMGs

Two A/Tk Rifles

Commander:- Ft/Lt Hillard,

RAF 1 Armd Cay Coy

Troops:- One Sec of 1

Armd Car Coy RAF

One Pl King’s Own

Det Sappers and Miners with lorry borne rafts

|

The systematic breaching of the bunds by the enemy troops made the task a

difficult one. SIN EL DHIBBAN ferry

was crossed by A Column in darkness on the night 18/19 May and as dawn broke on

19 May, the Column was still crossing the Regulator Canal.

At 0600 hrs the Regulator Blockhouse was attacked and captured with

little opposition. The flood water

from the breached bunds now played its part and Capt Anderson was held up by

difficulties in getting his MG’s and mobile transport through.

He made an abortive attempt to cross by raft but finally had to make a

detour on foot. His attack on the

blockhouse was in consequence three hours behind schedule time.

Thus deprived of his mule transport he had to wait for the support of One

Coy of Gurkhas from S Column before he could dislodge the Company of the enemy

which had been located in SAKHLAWIYA Canal and the palm groves to his front.

Furthermore, his guns were late crossing the ferry so by this time the

operation was five hours behind time.

Further complications were added by difficulties over communications but finally

the Column advanced and the enemy retreated without giving fight.

As a result of these delays and difficulties A Column by nightfall on 19 May had

only reached a point 1500 yds South of SAKHLAWIYA and approximately 1200 yds

from the Regulator and there it spent the night.

It had missed the battle but had made a very determined effort.

At 0415 hrs on 20 May, Capt Anderson advanced without his mule transport and

without artillery support on account of the flooding, reaching ANBAR RUINS at

approximately 0700 hrs whence again he left at 1045 hrs to take up the position

of the Column’s objective on the high ground NW of FALLUJAH.

S Column remained behind to dig in at the Regulator.

Turning now to Capt Graham’s Command, G Column left HABBANIYAH at 1700 hrs 18

May and then halted at Canal turn until it was dark enough to proceed up the

road to Hammond’s Bund. The

inexperience of the RIASC drivers caused considerable delay and the loss of two

vehicles during this part of the journey.

Hammond’s Bund was eventually reached at 2000 hrs.

Then began a weird fording of floodwater in the gloomy darkness as men trudged

through the gap in the road, pulling behind them fragile pleasure craft carried

over from Lake HABBANIYA, laden with stores and ammunition.

The mules, true to tradition, refused the ordeal and were left behind,

after which all weapons and ammunition had to be man handled.

Thus inevitable delay ensued, but the Column eventually arrived at Palm

Grove.

The town of FALLUJA was heavily bombed by the Oxford and Audax training aircraft

of the RAF at about 0500 hrs.

Pamphlets were dropped later in the morning, inviting the Garrison to surrender.

But as the Garrison went to ground as soon as our aircraft were heard, it

was improbable that these exhortations were read.

The town was again bombed at 1445 hrs, when the G Column troops were

creeping nearer to the Bridge which they reached with very slight opposition bt

1515 hrs and crossed by 1530 hrs. Consternation reigned in the town,

indiscriminate rifle fire went on until G Column reached their positions for the

skeleton defence of the town. The

few remaining enemy troops then surrendered and this Coy of Assyrian Levies,

although very thin on the ground, devoted themselves to digging in on the

perimeter.

During the morning of 20 May I visited FALLUJAH and ordered Cap graham to get in

touch with V Column which had landed from the air according to plan and without

incident and to co-operate in the stronger defence of the town.

The Commander of this column had shown remarkably little initiative

during the past 24 hours. Lt Col

Everett, King’s Own eventually took over command of the defences.

L Column meanwhile had been held by floods a mile or so NW of Notch Fall but its

infantry had joined V Column on foot.

Thus it was the aerial bombardment combined with the infiltration of the troops

from the South which were really responsible for our success.

To sum up the results of this battle, I think the cricket score board would have

shown something like the following:-

Iraqi Army: Frightened out

Bowler:

RAF

Score:

0

In

addition to the report above the reader’s attention is drawn to the fact that

early in the morning RAF Audax aircraft had cut the telephone wires from

Fallujah to Baghdad by the simple expedient of flying through them.